The game’s greatest delights exist within the wriggling mass of meat and gristle at the centre of the screen. In Carrion, you control the monster in a B-movie, breaking free from your cage within a vast subterranean research facility, to wreak your bloody revenge upon fleeing scientists and armed security. Think Ape Out, but with the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s answer to the devil in place of the ape. There’s a beautiful precision to the way your hideous form animates. Tentacles thrust outwards and grip perfectly to surfaces to support and propel you, while your central bulk stretches thin and re-combines again and again, like an abominable dough. I felt instantly in character as I steamrolled over my first humans in hazmat suits, gripping one in an oozing tendril, then dragging them towards one of my gnashing mouths. This is procedural animation at its finest, but it’s a detail you stop noticing quickly. What remains after, however, is the thrilling freedom of movement. Clicking in any direction makes your meatball marinara slide and slither swiftly thither, even if the direction you clicked is directly up. It’s liberating to play a 2D, side-scrolling game in which gravity is no obstacle. The result is that it’s never not fun to move around in Carrion - except for the anxiety about where to move, more on which later. In movies, monsters maintain their mystique by appearing only for long enough to terrorise the protagonists, before slipping back into the dark. Carrion proposes that what monsters do when they’re not onscreen is flicking switches. Or working out how to flick switches. Carrion lifts most of its structure from the Big Metroidvania Playbook, and that’s fine. You have to flip switches to open doors to progress to new areas. Some switches will seem inaccessible, but then you will gain a new ability that changes that. The powers are all pretty exciting, in fairness, gradually allowing you to do things like shoot webs, body-slam through barriers, turn invisible, extrude spikes, control humans with a parasite, and turn into a swarm of worms. They’re exciting - that is, until you realise you use each of these powers predominantly to reach new switches. Invisibility lets you sneak past lasers to reach the switch on the other side, parasitism lets you possess humans so they press switches on your behalf, and so on.

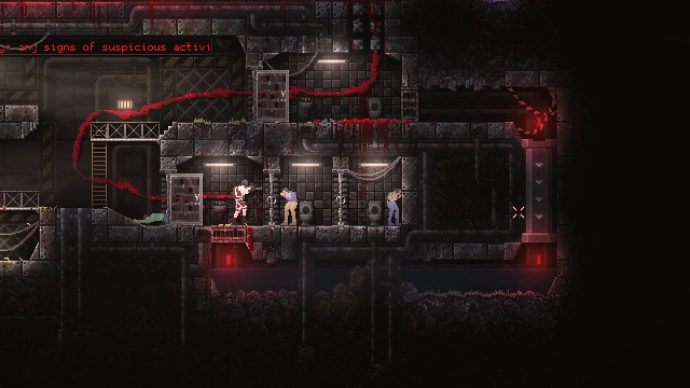

There is some light puzzling required to make progress, as only three of your unlocked powers are available at any given time. You can change which three you can access by altering your size, though. Eat meat and grow large like a Dad in quarantine (hi) and you can fire your spikes; fart some of your mass into pools of murky water to grow smaller, like a Dad in quarantine (hi), and the invisibility and wall-pound come back online. The culmination of your thoughtfulness is always yet another switch pressed, and eventually a new area of the facility breached. These same powers, of course, also come in handy during combat, as you thrust like a raw meat locomotive towards defenceless scientists and security forces armed with handguns, machine guns, flamethrowers and laser shields. I found the combat oscillated between the binary positions of ’trivially easy’ and ’entirely infuriating’. When it was easy, it was like I’d turned the cheats on in a naughty Amiga game, with pixel blood splattering in ways I’d be dying to tell the other kids about on the playground the next day. When it was difficult, it was normally because a later enemy, such as a mech, chewed through me with a chaingun in a few seconds, sending me back to a nearby checkpoint. It never felt like there was anything different I could have done to avoid a gunning, and so I’d do the same on the next life and win immediately, which felt in some ways worse. I think I would have preferred more difficult enemies which forced me to act more like actual movie monsters. Carrion offers ventilation tunnels to hide in, elevator shafts to skulk through, and grates to burst from, but little need to ever use them to hide from or lure enemies. Their AI is daft enough that they will put themselves in harm’s way without effort, and those you can’t overcome with sheer speed can normally be defeated with sheer size or power instead. Regardless, like its exploration and puzzling elements, Carrion’s combat is mostly fine. Any frustration I experienced was secondary to the frustration and anxiety I experienced in spending chunks of the game lost. Carrion has no map and no mission objectives. It never tells you where you’re going, how to get there, or what you need to do next in order to advance.

Some of you reading this will be cheering at this point, for a game that won’t hold your hand. I personally like holding hands, because it makes me feel gooey in my tummy and because I trip over all the time. But I’m not philosophically opposed to a game that forces me to stand alone. The lack of exposition is especially admirable. I just don’t think the rest of Carrion’s design supports this laissez-faire approach. The facility your bloodworm buddy is exploring encompasses research labs, nuclear reactors and more, but it’s almost all made out of grey metal. Every area is also a warren split into discrete screens, often with three, four, or five different exits. It is easy to end up looping through the same rooms over and over by accident, and then you’ll do it on purpose to impatiently hunt for whatever you might have missed. All in all, this need to mentally map your surroundings seems counter to your character who, remember, is a big meaty sick that moves at the speed of a missile.

Worse, progress is often tied to entirely arbitrary goals, such as looking at a nondescript bit of wall in order to trigger a door to open, or squeezing your writhing mass into an easily-missed hole. The result, for me, was anxiety. A low background hum of “did I miss something”, combined with the high notes of being unable to find the next new area. It was enough to shade my entire experience with Carrion, turning a pleasant enough Metroidvania with a one-of-a-kind protagonist into something I felt like I was struggling to escape from. Your mileage may vary. But for me, I was happier with the GIFs.