Your job in this game is to disassemble derelict ships in orbit high above the Earth, which over the course of several dystopian centuries has become a perilous scrapyard of useless cosmic junk. You are the little Dutch boy with his finger in the dyke of entropy, one of an unseen army of corporate wage slaves tasked with restoring order to chaos by slicing and dicing retired shuttles into small enough chunks that they can be hurled into a big space furnace and turned back into something useful.

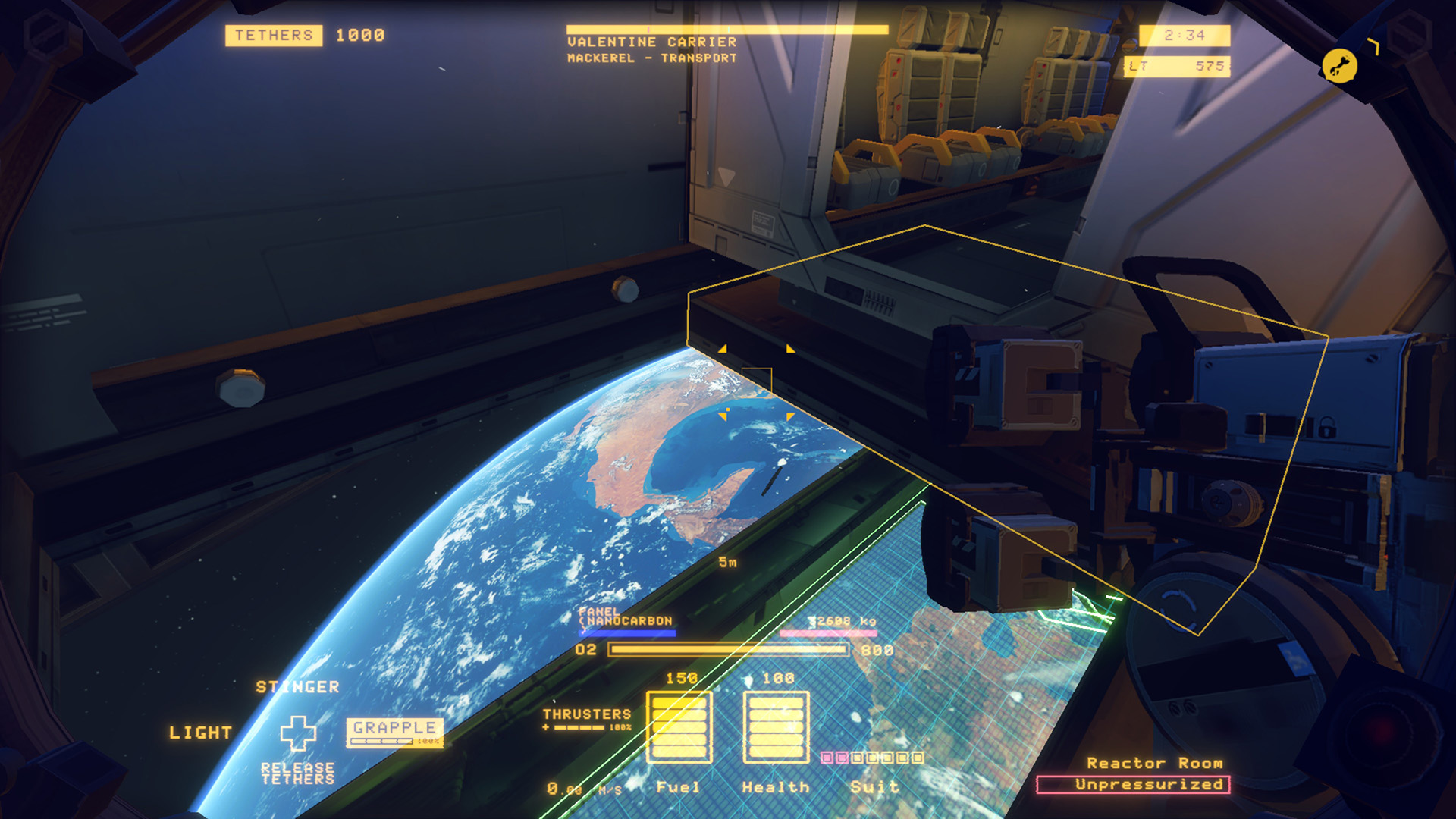

Like clearing rocks or painting fences, the simplicity of your mission lends it a zen-like quality, aided by the incubating soundlessness of space and the vast spectacle of the planet Earth far below. Carving up spaceships is profoundly satisfying. I hope that this is what the afterlife is all about, that when I die, old and happy and surrounded by my dearest friends, I wake up right here in front of a half-dismantled cargo ship, armed with a fancy tin opener. Recycling a spaceship is less straightforward than just hacking away at the hull like it’s a big easter egg. The vessels you’re dissecting are intricate metal puzzle boxes, constructed from interdependent parts that must be removed in the correct order. There are fuel lines that run through the ship like veins, still turgid with flammable juices and waiting to ignite. There are fat tanks of coolant lurking behind cabin walls like subcutaneous blisters, live wires and reactor cores that tick like time bombs the instant they’re removed from their moorings.

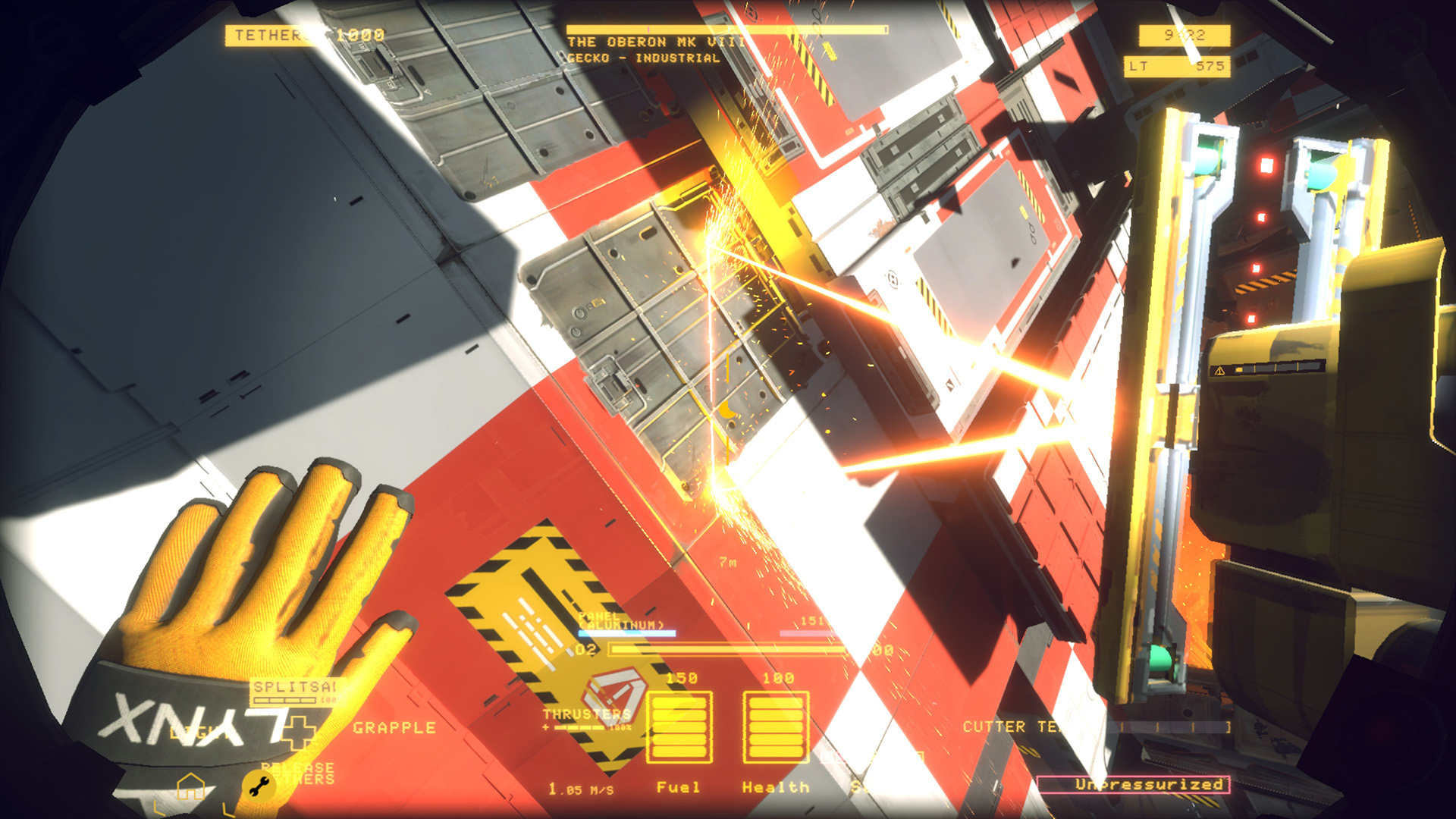

This is a zero-gravity surgery game in which you play from the perspective of the scalpel. You spend each run stripping ships of their raw materials using a suite of cutting torches, rope-like tethers and a gravity gun, laser-carving neat squares into softer panels to give you access to the ship’s metal guts. A scanner in your helmet reveals the ship’s schematics, including its skeletal rib cage, and the weaker support points that when cut will separate it into easy to manage chunks. Your gravity gun obeys Newtonian physics. Lasso a piece of the ship that’s heavier than you, and you’ll move around just as much as it does when you push against it, like pushing against a rock with a canoe’s oar. Anything lighter can be moved around with ease, and really large chunks can be tethered with magic space-ropes that pull with a small but constant force, very slowly inching massive panels away from the body of the ship. It’s a robust and precise physics simulation that always feels pleasant to move around in, and reacts as you’d expect it to at any time. Carve away enough of the ship and you’ll notice that the entire thing will have begun to capsize around its new centre of mass while you were inside it, listing drunkenly as you extract heavy thrusters like they’re rotten wisdom teeth.

Deconstruction is perilous. Accidentally slice into a pressurised compartment and it will violently decompress, turning one corner of the ship into a rapidly expanding cloud of metal shards, atomising your soft flesh body and spilling the ship’s most valuable components. Instead, the safest approach is to creep in through the airlock to safely depressurise compartments from the inside. Ship interiors are cluttered crypts, some of them pitch dark, others lit by blinking emergency lights and haunted by the mundane ephemera of interplanetary travel, floating garbage left behind from journeys past. Taking ships apart feels funereal, like unscrewing the handles of a coffin. There are only two basic ship types in this version, their insides randomised in terms of room configurations and collectibles you can find: things like repair kits, additional oxygen and world-building audio logs. Over repeated runs – it takes around 12 hours to see every configuration – you’ll start to build a mental blueprint of their various crawlspaces and weak points, gradually becoming more efficient at ransacking their most valuable parts in a shorter space of time.

Maximising each run’s profit is important, as you not only owe your employer precisely one billion credits – a consciously impossible amount to ever pay down – but each day you accrue even more debt in rental fees for your tools, lodgings and spacesuit. Death offers no release from your employment contract, as your benevolent corporate overlords own the rights to your DNA sequence and can clone you back into existence at great expense to your progeny. Hardspace is a satire of corporatised space travel, a commentary on the evaporating rights of a dehumanised modern labour force. It’s also a quiet investigation of a liminal space. The more of the ship you dismantle, the less apparent the boundary between the inside and outside becomes, until that boundary has entirely vanished, and what’s in front of you is no longer a ship with a hole in it, but a hole with a ship in it. A swirling mess of deconstructed parts where a thing used to be.

It’s that melancholic pang you get when moving house, after just enough furniture has been removed that you no longer recognise the rooms as your own. Or when you’ve eaten a sandwich, and the sandwich isn’t there any more. Or when you delete a confusing sandwich analogy, but now you feel hungry for a sandwich. Carving up a spaceship until it breaks into pieces and then throwing all of those pieces into a giant furnace is unexpectedly mindful and focusing. I can’t get enough of it. Hardspace: Shipbreaker speaks to the part of your brain that, when sufficiently bored, wants to very carefully take something apart until every bit is laid out neatly in front of you. A brilliant and therapeutic space simulation, and a quiet celebration of the simple act of deconstruction.